My starting point for the ten books in this series has been a book structure to which I have added elements of some aspect or essence of the architect's work and this is particularly relevant with the two book sculptures Le Courbusier and Libeskind.

Around 2002 I made a couple of vellum cube books which contained divisions like chapters inside.

I liked the way they closed down to a complete white cube. This gave me the idea to use this sort of structure for Le Courbusier, as it reminded me of his white concrete box-like villas (often on stilts).

Le Courbusier was also interested in proportional theory in architecture and saw his Modulor system as a continuation of the tradition from Vitruvius, Alberti and Leonardo da Vinci. He introduced the modernist open plan and split level floors and made housing more affordable by using simple low cost reinforced concrete and prefabricated construction methods.

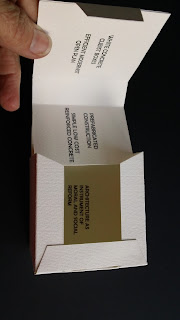

Using heavy 300 gsm Fabriano watercolour paper, I made a box but left the back and lid section free. The internal construction of the book has been adapted from one of Le Courbusier's internal construction plans. The pages are like two floors that overlap but create a split level, with one shorter in length than the other, like two mezzanine floors.

As the book closes, the shorter split level floor/page sits above the lower floor/page and then closes into a white cube.

Daniel Libeskind's Jewish Museum in Berlin was built in 1989-99 and I think it is one of the most remarkable pieces of architecture. It takes the shape of a zinc clad dislocated Star of David with a concealed entrance. His deconstructivist work suggests fragmentation, alienation, disorientation, oppression and is intentionally disturbing.

For this book I again made a box-like structure with angular slanted ends. I thought it appropriate to use the skin of a once-living creature - in the first version I used calfskin vellum and this time I used goatskin parchment. I cut pieces of aluminium shim to size, scored them with an embossing tool and attached them to the parchment. I cut a jagged opening in the top, slit the aluminium and rounded it under the opening.

The page of text was placed into the bottom of the box and can only be read with great difficulty, either peering through the slash in the top or lifting the bookcover-like flap at the end and peering into the narrow opening of the box.

This brings me to the end of the Ten Books on Architecture. If you have any questions about materials or techniques that I have used, please ask me. You can contact me by adding a comment or sending me an email through the contact section of my website.